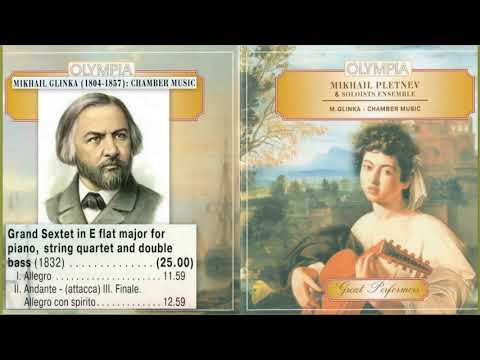

Mikhail Glinka – Grand Sextet in E Flat Major for Piano, String Quartet, and Double Bass, M. Pletnev & Soloists Ensemble (Mikhail Pletnev, piano; Alexei Bruni, violin; Mikhail Moshkunov, violin; Andrei Kevorkov, viola; Erik Pozdeev, cello; Nikolai Gorbunov, double bass)

I. Allegro – 00:00

II. Andante (attacca) – 12:01 —– III. Finale. Allegro con spirito ( 18:54 )

Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka (1 June [O.S. 20 May] 1804 – February 15 [O.S. 3 February] 1857) was the first Russian composer to gain wide recognition within his own country, and is often regarded as the fountainhead of Russian classical music.

‘The father of Russian music’ is the description by which Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka has become known throughout the world. The term is not strictly accurate, because there were many Russian composers before him, at least since the time when Tsar Peter the Great began to cultivate West European culture. Whereas these composers mostly tried merely to imitate foreign music, however, Glinka was the first genuinely Russian composer of genius – the first of a distinguished line. He always aimed to compose in a Russian manner; paradoxically, in spite of this intention, his music too was West European from a technical point of view.

Glinka was born into a rich, upper middleclass family in Novospasskoye near Smolensk and he received a first-class school education supplemented by studies of the piano, violin and flute. At that time there was no conservatory in Russia, so when he was 13 he moved to St. Petersburg to study privately with the Irish piano virtuoso John Field. In the Russian capital Glinka encountered many representatives of Russia’s intellectual elite. Before Glinka finally devoted himself to music he enjoyed a brief career (not exactly distinguished by overwork) in the Ministry of Transport. His doctor then advised him to go to a warmer climate on account of his weak health, and his years in Italy, Austria and Germany (1830-34) were made easier by his exceptional gift for languages. In this period he completed his education, became acquainted with musicians such as Berlioz, Mendelssohn, Bellini and Donizetti and received musical stimuli of decisive importance; when he returned to his homeland he was firmly convinced that he would become an opera composer in the manner of Bellini or Donizetti. Glinka’s first opera was A Life for the Tsar (which he originally intended to call Ivan Susanin) was premiered with great success in 1836: it was the first Russian opera in the modern West European style, integrated with Russian folk-music. Glinka immediately wanted to write another stage work but Pushkin, the intended librettist of Ruslan and Ludmila, was killed in a duel and the opera was not well-received by the public.

After the opera’s premiere in 1842 Glinka lost his grip completely. He journeyed to Western Europe, where he led an ever more eccentric life. He lived in Spain for two years and in Warsaw for three. Glinka died in Berlin in 1857.

As a composer Glinka was basically self-taught, which is all the more remarkable in the light of his masterful command of the orchestra. He assimilated his compositional craft from the tireless study of scores and from practical music-making; he studied singing as well as instrumental music, and for a while he worked as a conductor. Glinka’s work was clearly influenced by foreign music – especially Italian music – but this is mostly confined to the technical aspects; the spirit is entirely Russian. Glinka’s own influence on foreign composers can easily be overlooked. He was responsible for an important innovation in musical language, the Tchernomor scale (a whole-tone scale which derives its name from the evil magician Tchernomor in Ruslan and Ludmila). Among the composers influenced by this scale was Debussy who, like Ravel, studied Russian music in great depth and who was influenced by it far more than is generally realised.” (from album notes)